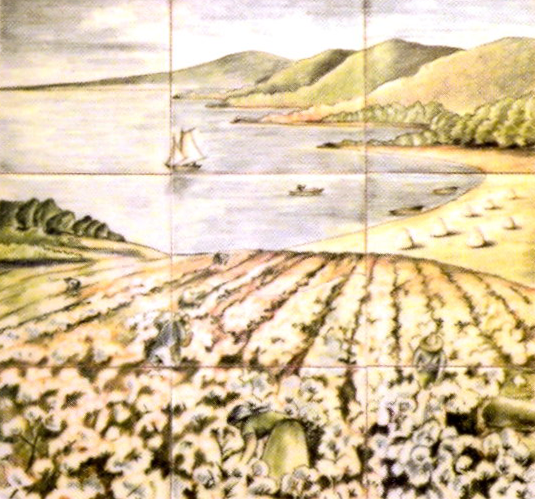

An interesting aspect of the population of Honduras in the nineteenth century is that, geographically speaking, the country remained relatively stagnant. For many generations, highlanders rarely migrated from their villages. The country did not experience major demographic movements until the end of the century, when companies attracted people to the Caribbean coast, with well-paid job offers in the banana and fruit plantations.

Estimated population of Honduras from 1820 to 1870 (in thousands)

|

Years |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

|

Population |

135 |

152 |

178 |

203 |

230 |

265 |

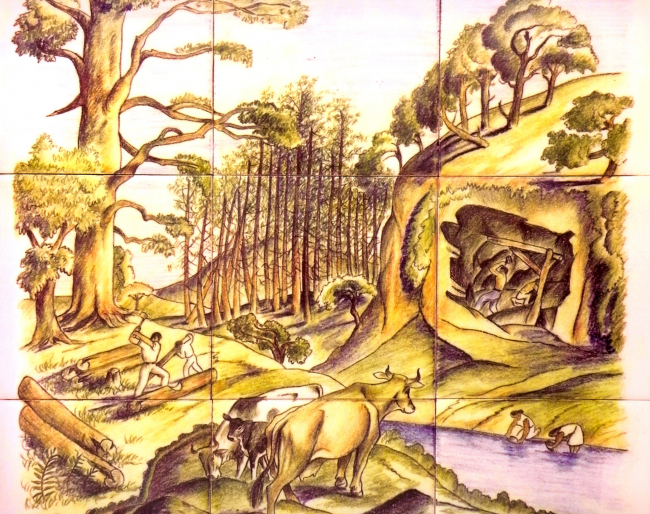

This entire population has lived in a peculiar topography, which has proved detrimental to progress in two ways: low population density and relatively high transport costs between towns and ports.

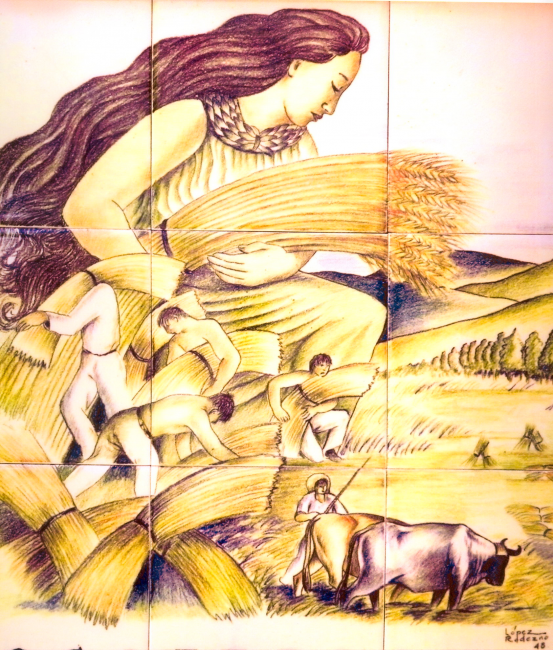

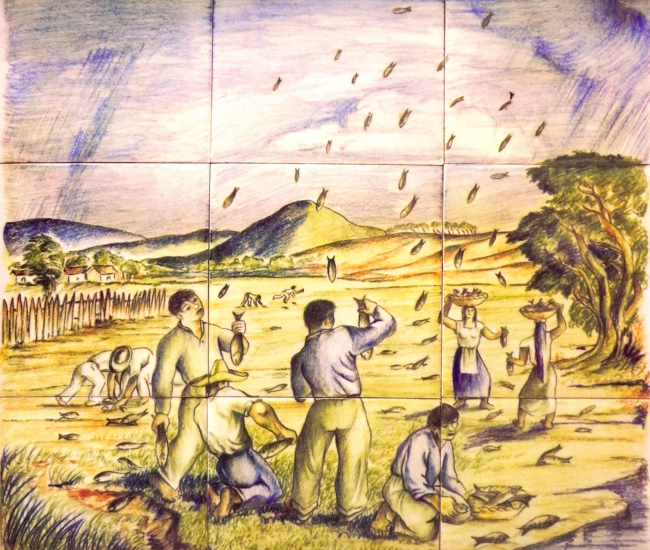

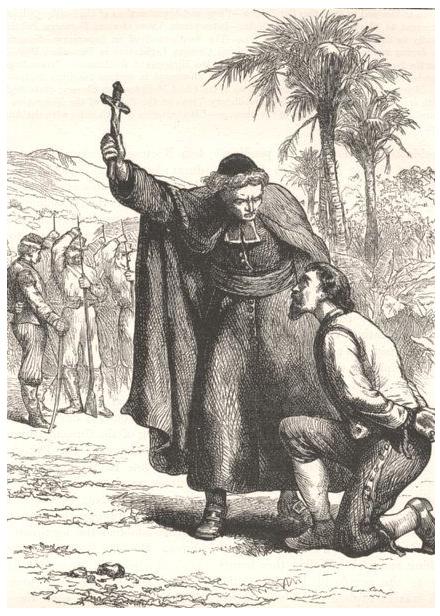

In terms of social structure, the indigenous population in the nineteenth century remained a majority and were identified through language, clothing, community membership and subsistence agriculture in villages or communal lands.

Another group is the "ladino," which would presumably means someone of mixed race, fully Hispanic in culture, who had the right to escape the forced labor of the indigenous were submitted to, and who potentially deserved to share the exploitation of the indigenous, as a foreman, labor recruiter, labor merchant, manager, and so on.

Likewise, "mulato" was more frequently used to refer to populations of virtually identical mixture to the previous one but whose position was lower in the social scale or characterized by insubordination regarding their settlements, tax and labor obligations, or the composition of the household.

Thus, three of the large labels assigned to those of mixed ladino, mestizo, and mulatto origin had clear socio-political connotations that went beyond any one of the following racial hereditary scheme, and these meanings were changing over time.

Another group, the "zambo" (Indian-African), was almost always used to refer to the zambos mosquitos, which constituted a clearly political and military assertion without any pretense of an objective racial basis.

The entry of rich mestizos into the ranks of white society via marriage was part of that social dynamics, as part of the advance and consolidation of the state and the participation of these groups in the export economy especially with those products no longer considered traditional such as coffee.