Encouraged by the incentives to immigration, many Europeans arrived in Honduras, especially English, Germans, Italians, French, Irish and Spanish. From the Middle East came many Turks, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese, who escaped the decomposition of the Ottoman Empire, and were in search of better opportunities. The majority established themselves on the Caribbean coast, especially in Ceiba, which soon became the most important economic pole after Tegucigalpa.

On the other hand, the banana boom became a real economic enclave and as such, it was closed and exclusive. The small local bourgeoisie that had begun to form on the Caribbean coast in the late nineteenth century, linked to the cultivation and sale of bananas, disappeared. The banana companies recruited peasants and workers from other Central American and Afro-Antillean countries. But in the executive cadres only American technicians and professionals were employed. With their own network of stores, and the payment in bonds to their employees, who were forced to buy in their own warehouses (Commissariats or "String Stores"), they concentrated in the banana enclaves virtually all the profits, preventing the development of a Honduran internal market. The European and Chinese immigrants, but mainly the Lebanese, Syrian, or Palestinians took advantage of the few commercial spaces that were left open.

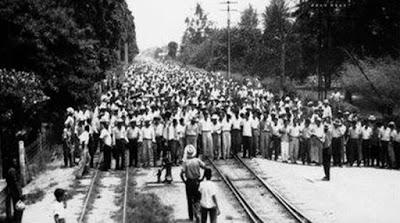

Emergence of the workers movement

The first mass concentration of workers in the history of Honduras took place when the interoceanic railway works began in January 1869. The early stoppage of the construction activities prevented the development of the first nuclei of an organized movement of workers. On March 10, 1909, the first protests against the wage regime imposed in the mine of Rosario, the miners agreed to decree a strike which was repressed by police intervention.