The historiography related to the conquest of Honduras is characterized by its violent nature, as a consequence of the confrontation between the same Spaniards for their personal ambitions and the resistance opposed by the natives to the plundering and exploitation, both of their natural resources and their labor force to which they were subjected.

This process of submission was seen from the contempt for their culture and the destruction of their cultural, economic, political and religious worldview. The particularly brutal participation of Gil Gonzales Davila, Cristobal de Olid, Pedro de Alvarado, Francisco de Montejo, Alonso de Caceres, among other Spaniards, should be highlighted. The sense of appropriation, no matter what the recommendations in the Reales Cedulas were, had a purpose, in the conqueror there was an idea that was to organize the territory according to an eventual natural strait that would facilitate transoceanic trade, an idea that would gain strength soon after and that would become a recurring illusion in Honduran history.

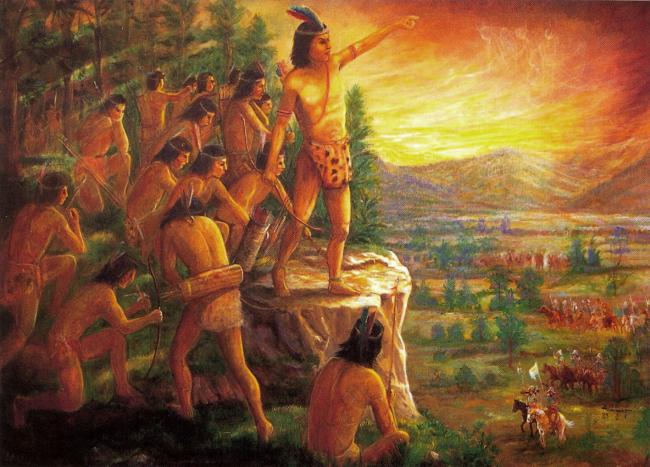

Indigenous Resistance. Lempira.

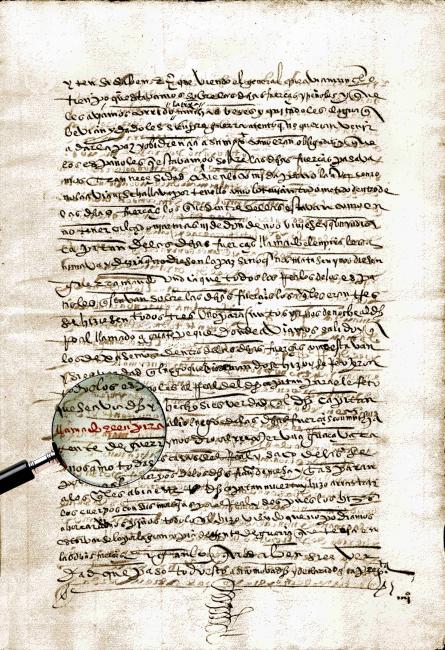

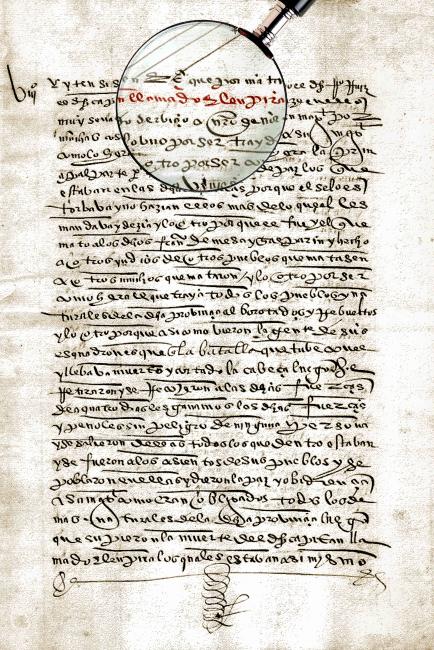

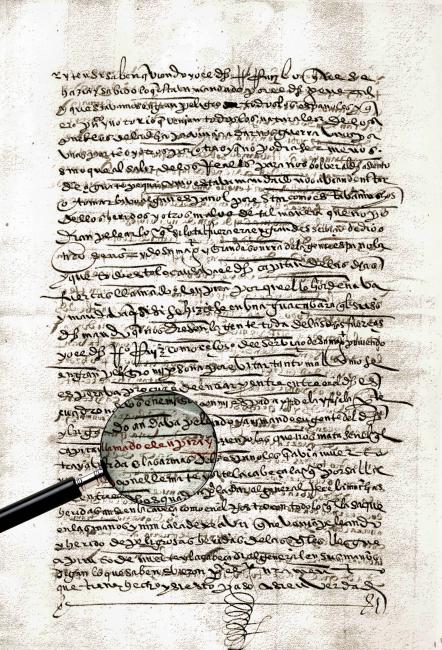

The indigenous peoples of the continent who fought against the Spanish occupation asserted their right (now universally accepted) to defend the self-determination of the peoples. More than a problem of fighting for the sovereignty of a country still in formation and which was rather the conquering project, they fought for something more radical, for the right of each people to decide and shape its past, its present and its future. There were indigenous leaders who represented the determination of their Friars: Lempira, the Lenca chieftain, led this heroic struggle in Honduras. The historian Antonio de Herrera, in his Decades of the New World (1616) tells us about his deeds:

Lempira, was about 30 years old, of strong complexion and proven courage, so daring that it seemed impossible to kill him in battle. In the Lenca style, he was fortified by a considerable indigenous population in a crag (or hill), possibly in Cerquin and with enough supplies to face a prolonged siege. The Spaniards had to resort to a ruse to kill him while they were talking about peace. There is another version according to which he died in combat. His resistance was internalized in the popular memory.

Other fighters were Cicumba, Tolupan, in the Sula Valley, Copan Galel in Ocotepeque, Benito in Olancho. The Spanish administration had created the Governorship of Honduras in 1527 but at first they had only occupied the northern coast, to settle inland they needed to defeat the natives and found cities. This is what Pedro de Alvarado who founded San Pedro and Gracias (1536) and Francisco de Montejo with Alonso de Caceres who founded Comayagua (1537) did. The indigenous resistance was generalized, especially in the central and western area, the Lenca area, under the inspiration and example of Lempira.

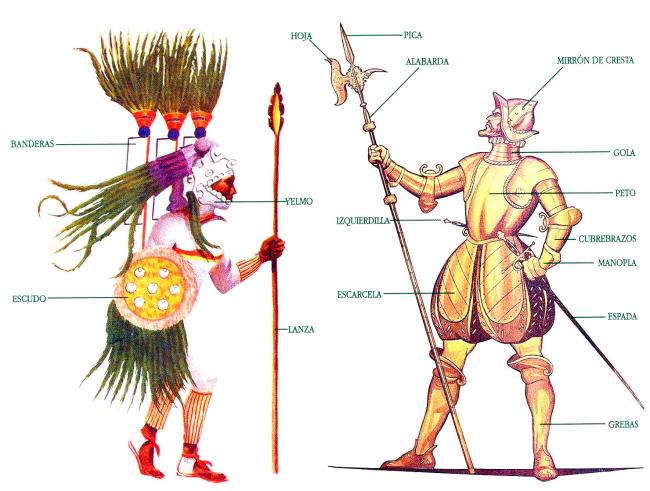

The chronicler Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas describes him as "of medium height, back and thick limbs, brave and courageous; of good reason [...] and he died from thirty-eight to forty years old". "He was so courageous, that he never showed weakness and never wanted to listen to the ways of peace that the Castilians offered him; before he had so little of them, that from his strong point he said many insults". He organized his uprising in Cerquin, and concentrated his forces "in the Sierra de las Neblinas". He went to the battle with his head covered by a "helmet, that in the way he used it was, very elegant and extravagant", although at the moment of his death he was wearing Spanish clothes of some of his victims.

There was no truce in the war, but finally he fell, according to the chronicler Herrera, from a harquebus shot in the forehead by a soldier who was on the croup of a horse, or in a combat in which he faced Rodrigo Ruiz who, according to his statement, "cut his head off. When contemplating his death, Herrera writes, "great uproar and confusion arose among the Indians, because many, fleeing, fell through those mountains and others then surrendered. Lempira's death was the end of the indigenous resistance: the Indians disbanded and soon surrendered, which was the beginning of "peace " in Honduras.

Simultaneous with the military and violent conquest, there is the demographic cataclysm, which as far as known, never before, in any other part of the world, so many had died in such a short period, as the consequence of a hidden and silent agent called smallpox.

This and other diseases introduced during or after the conquest were devastating in a land where they were unknown and whose population had no immune defenses or specific resources to fight them.

Becoming an epidemic, the disease broke out with such force and spread so quickly that it worked actively against the indigenous resistance, thousands of lencas, chorties, chorotegas, tolupanes, pech, among members of other groups died. Among other aspects, it is possible to assure that the disease traveled faster than the Spanish invaders and arrived to places where they would still take a long time to reach personally, that is, in territories of La Taguzgalpa, to mention an example.